What do sanctions help achieve? An expert explains

来源:World Economic Forum;发表于:2022-04-14;人气指数:330

What do

sanctions help achieve? An expert explains

https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2022/03/what-do-sanctions-help-achieve-an-expert-explains/

Sanctions: The

relations between the different key powers will be shaped by economic warfare

first and foremost.

Image: UNSPLASH/

Jason Leung

22 Mar 2022

Jonathan Hackenbroich

Policy Fellow,

European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR)

Abhinav Chugh

Content and

Partnerships Lead (Expert Network & Content Partners), World Economic Forum

*Economic sanctions

imposed against Russia for invading Ukraine are the most comprehensive and

coordinated actions taken against a major power since World War II.

*Multinational

companies across all sectors are pulling out of the country, taking their

products, services, and jobs with them.

*Russian citizens are

seeing their purchasing power and livelihoods sharply eroded because of the

depreciation of the Russian ruble.

Economic sanctions have

been used as a tool of war for centuries. In 17th- and 18th-century Europe,

economic sanctions were frequently implemented by countries at war. They included

prohibitions on trade, the closure of ports against enemies, and bans on

trade in certain commodities. Economic sanctions continue to play an

important role in the response to terrorism, nuclear proliferation, military

conflicts, and other foreign policy crises.

The primary objective of

imposing sanctions is to deter bad behaviour, enforcing economic punishment on

the targeted country, and to force rehabilitation, or changed behaviour by that

country. However, the success of sanctions depends on their enforcement and

effectiveness. Sanction efforts are most effective when coordinated and

implemented multilaterally with allies, and poor design and implementation of

sanctions policies often leads to them falling short of the desired effects.

After Russia

initially invaded Ukraine in February 2014, the United States imposed a series

of sanctions designed to punish and weaken the Russian economy through

restrictions on trade and finance. However, these sanctions failed to deter

further aggression and we're witnessing a worsening conflict. Given these

circumstances, we're now observing the most severe and coordinated sanctions

effort led by the United States and the European Union to deter further Russian

military advances.

In the long term, all

these measures will have dire consequences for the Russian economy. We

asked Jonathan Hackenbroich, Policy Fellow, European Council on Foreign

Relations to provide us with some context relating to the historic use of

sanctions, insights into how the current sanctions policies are being shaped by

geopolitical movements of the past decades, and what various leaders and

policymakers need to take into consideration as they work on efforts to absorb

the economic aftershocks of sanctions.

The legitimization of

sanctions as an economic weapon

How have sanctions as

an economic weapon come to be seen as an alternative to military action?

Jonathan: Economic

sanctions have been a tool of statecraft, alongside military tools, for some

time. But the world has entered a new phase of globalization characterized by

the increasing use of economic tools for geopolitical purposes (or geo-economics)

and systemic rivalry. We may see proxy wars and indirect military

confrontation, but the relations between the different key powers will be

shaped by economic warfare first and foremost. This is chiefly because these

powers will try to avoid direct confrontation to fend off the use of nuclear

weapons and because they can more easily use asymmetric dependencies in economics

– for example access to US financial markets – to pressure the other.

We can see precisely

this preference for economic tools to avoid nuclear war play out currently in

most great powers’ relations with Russia over its aggressions in Ukraine. In

economic warfare, tools include everything from positive economic instruments,

such as trade deals, to coercive ones, such as curbs on imports, formal

sanctions, and informal sanctions (including so-called “popular boycotts”) –

from investments in strategic competitiveness to regulations designed to change

company behaviour.

Were economic

sanctions successful in the 20th century? What were some of the

false assumptions relating to sanctions?

Economic sanctions

can only be one tool in the toolbox for enforcing global peace. While they have

imposed great economic pain in the past, they have been more unsuccessful than

successful in achieving their political goal. The key determinant of sanctions'

success is how the sanctions target (in this case Russia) versus the cost of

changing its behaviour (withdrawal from Ukraine) compared to the economic cost

imposed (that is disconnection from international financial markets).

Sanctions on Iran

were successful in bringing the country back to the negotiating table – and

indeed to agree to the Iran nuclear accord – when the Obama administration

clarified the sanctions goal: it stated it was not regime change (something

Tehran would have always considered to be more costly than sanctions pain), but

to persuade Iran to refrain from building a nuclear weapon.

In the past, there

were instances when sanctions or the threat thereof, were successful in

changing the target’s behaviour: when the League of Nations threatened

sanctions against Yugoslavia under Article 16 in 1921 to keep it from seizing

land from Albania, for instance, Yugoslavia did not do so. There are other

examples, especially when sanctions goals were not overly ambitious. But a

prominent one might be the end of South Africa’s Apartheid regime, where

sanctions had an important role in achieving success.

The impact of

sanctions on global governance

What has shaped the

new dynamics of economic sanctions in recent times?

The US war on terror

in the 2000s revolutionized sanctions policy. The US used its centrality in the

world’s financial system to coax banks around the world to refrain from facilitating

terrorist financing, close down accounts and freeze assets that Al Quaeda could

no longer access for its operations.

Targeted sanctions

became much more central to sanctions policy after the crippling sanctions on

Iraq during the 1990s, which primarily had the effect that the Iraqi people

suffered, but did not succeed in fundamentally changing the calculations of the

Iraqi regime. Donald Trump’s unilateral policies of maximum pressure failed in

changing Iran’s or Venezuela’s policies, even though they brought back

comprehensive sanctions.

The latest Russia

sanctions now are a combination of targeted measures against oligarchs, massive

financial sanctions and longer term trade sanctions, put in place by a broad

coalition of many key countries of the international economic system.

What could be the

possible consequences of the current global alignment on economic sanctions

against Russia? Could this lead to “expansionary autarky”?

An increasing share

of world trade will become power-based rather than rules-based. This is the

more important trend. A country like Russia will have to deal with the

difficulties that come with disconnection from large parts of the international

financial system and rapid, and broad decoupling.

China is, of course,

closely watching the West’s sanctions playbook, and one lesson is that US power

and control over the world economy’s key chokepoints remains unparalleled. But

using the same playbook on China would be extremely difficult for the West.

Europe’s energy dependence has shown the continent can be vulnerable. The key

question might be how far-reaching the lessons will be that Europe draws from

this.

Navigating a global

economic reconfiguration

What is the role that

developing economies play when such geo-economic reconfiguration takes place?

What can they do to reduce the economic fall-out from sanctions?

Developing economies

are much more concerned by shortages of essential goods, even at a time when we

primarily discuss Europe’s dependence on Russia’s energy. It is in developing

countries that we will see, and are already starting to see, prohibitively high

food prices and shortages which impact their populations most.

Those that will cope

best tend to have best networks for economic diplomacy and have the ability to

substitute more imports locally. But it will be very difficult for some. More

generally, developing countries may have to cope with the (out-)flow of capital

into safe havens in developed economies, and it is possible they stand less of

a chance to attract parts of global supply chains and production, as the

world’s economic hubs care more about security of supply chains than the

highest degrees of efficiency.

But the picture tends

to be more complex than that overall. Some of them – especially those

geographically or value-wise close to certain developed economies – might

benefit from near-shoring efforts as the global trade order becomes more

polarized. And if (mostly partial, but at times more comprehensive) decoupling

advances, especially if the world’s big markets become more difficult for each

other’s companies, different players of the so-called developed world may turn

to parts of the developing world much more. We’re already seeing that many

countries in Africa are hedging their bets when they abstained in the UN GA

vote over Ukraine.

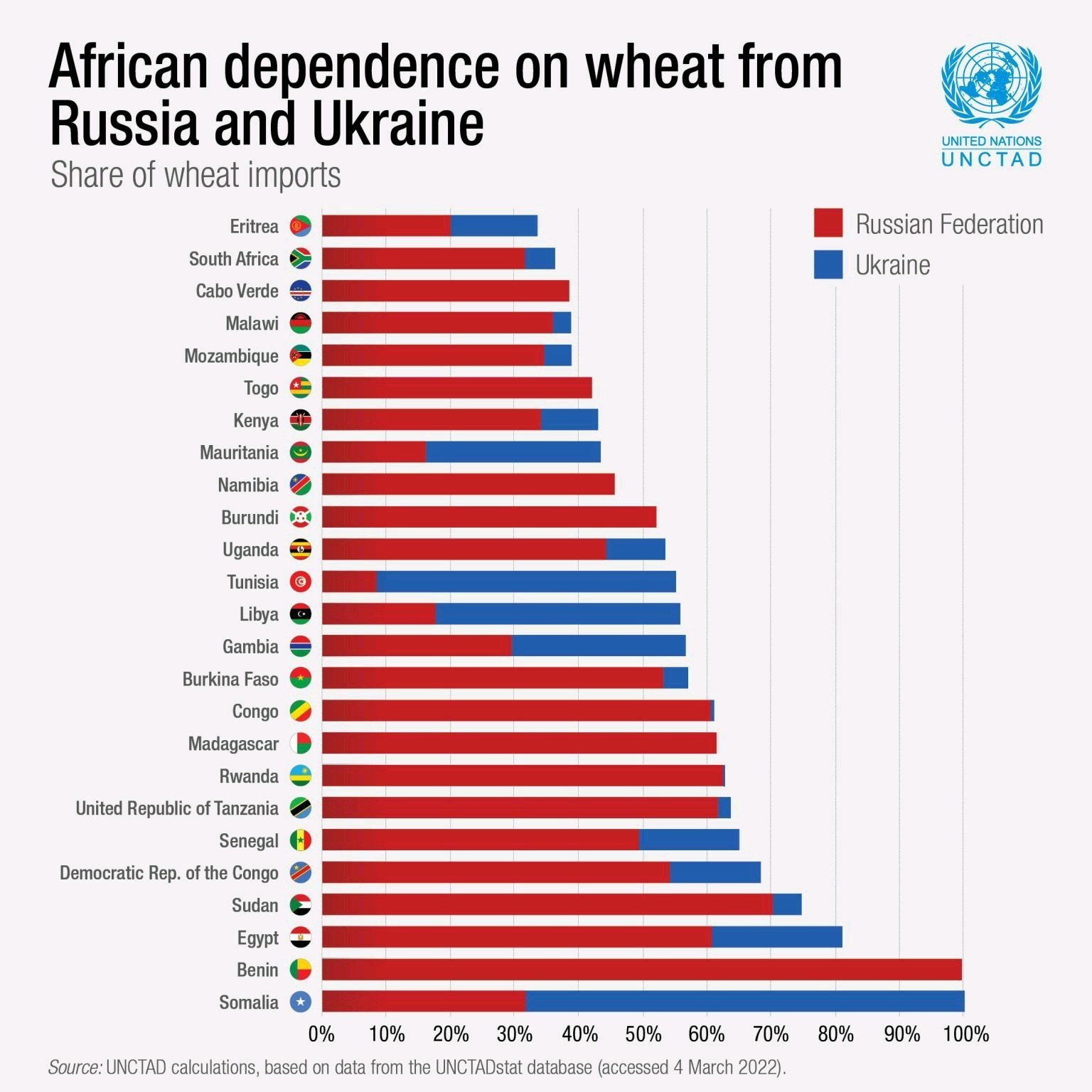

African dependence on

wheat from Russia and Ukraine

Image: UNCTAD

What kind of measures

would policy makers and private corporations need to undertake in the

medium-term when the global economy starts to move towards correction after

taking a hit from the economic damage of sanctions?

Much is still in

flux, and depends on how the current imposition of sanctions and the current

war play out. It is safe to say that many companies need much greater

geopolitical expertise and will have to factor in geopolitical risk to a much

greater degree in their investment and trade choices.

This is a particular

challenge for SMEs, but even bigger corporations may need more political

competence. There will also be a need for permanent geo-economic dialogue

between policymakers and private corporations. The EU, for instance, has put in

place its public-private Industrial Forum aiming to ensure the EU receives the

information from companies it needs for effective implementation of the digital

and green transitions. But it lacks such a format for the third big change the

world is undergoing – that is the geopolitical one.

In general, state

policies and corporate policies will be more intertwined in a world in which

geopolitics and trade are much more intertwined. Both sides will have to

develop innovative forms of dealing with a trade world that will be more split

into power-based and rules-based, and more polarized between democracies and

autocracies, as well as many countries that will try to hedge between these two

worlds.